Whether it’s because of the flexibility of online learning during the pandemic, the ubiquity of cell phones at all hours of the day, the short duration of social media clips or a combination of all that and more, teachers and students both agree that today’s students are having more trouble paying attention.

Teachers are then faced with a dilemma: continue traditional classroom methods that may lead to students zoning out or find inventive ways to engage them.

For many Chapman teachers, the latter is the goal.

Math teacher Rachael Fowler said that the 90-minute block presents problems for students and that she deliberately breaks her lessons into smaller sections.

“When I plan my lessons, I try to do 30 minutes of one thing and another 30 minutes of something else to break it up so that they don’t have to be paying total attention the whole entire time,” Fowler said.

English teacher Holly Hollifield looks for ways to keep students focused through interaction.

“Forcing them to interact in some way, whether it’s writing something down or popcorn reading, (is helpful because) then they know they have to pay attention more,” she said.

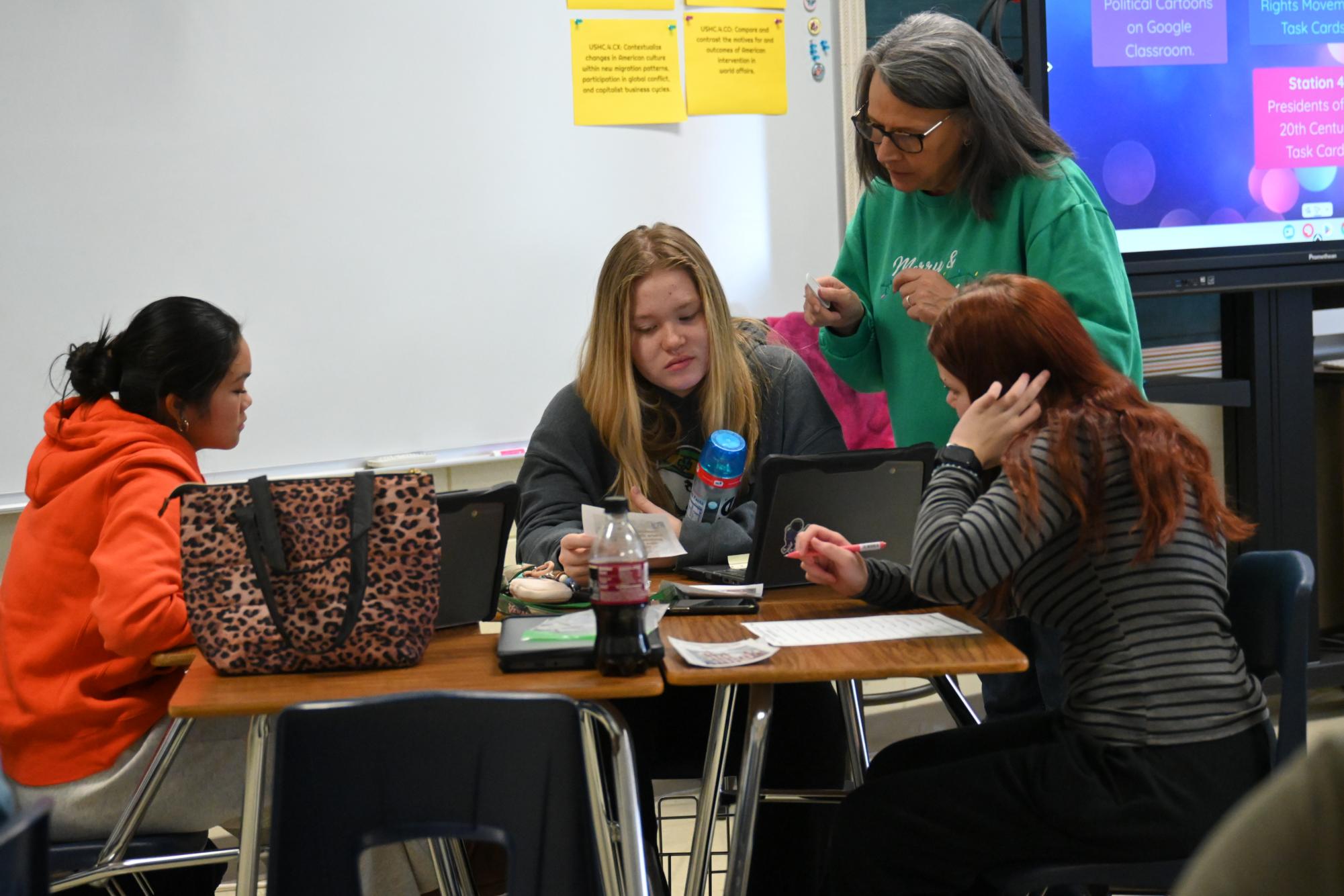

Social studies teacher Fara Stewart has made adjustments to her teaching style to accommodate students who have been raised in a social media environment.

“I try to limit lectures and direct teaching to 10-15 minutes,” she said. “I joke that most attention spans are about the length of a TikTok video.”

For Stewart, it’s not just about limiting her speaking but about allowing students seemingly contradictory opportunities: time to work alone and time to work together.

“I have found that it is easier to create assignments that allow students to learn at their own pace,” she said. “By creating self-paced assignments, it is easier to help students after absences. Students who lose focus easily don’t become completely lost if they are working at their own pace.”

Stewart is also known for her classroom practices that encourage collaboration.

“Group activities or learning stations allow students to communicate with others and are effective ways to overcome lack of focus,” she said.

Students such as senior Elizabeth Lawson say that they’re aware of their attention issues and find teachers’ willingness to change to be helpful.

“I definitely notice myself losing track of what’s going on, especially when things are repetitive or I’ve been sitting for a long period of time,” she said. “However, when I’m doing interactive lessons or discussions, I’ve noticed that I don’t lose my attention.”

Freshman Luke McAlister is emphatic about his desire for teachers.

“Teachers need to make things more exciting,” he said.

Although Chapman teachers work hard to engage their students, the onus isn’t entirely on the teachers to solve students’ attention issues.

Part of the reason students struggle to pay attention is because their attention is divided at all times.

School is no exception: A website takes a while to load so students check their phones and scroll through social media.

This may seem like a harmless example of multitasking, but a large body of research consistently shows that humans are generally not able to multitask. What students may think of as a harmless scroll while waiting on a website has detrimental effects.

Writing for the “Harvard Business Review” in 2010, psychology professor Paul Atchley identified the downside to such “harmless” activities.

“Based on over a half-century of cognitive science and more recent studies on multitasking, we know that multitaskers do less and miss information,” he said. “It takes time (an average of 15 minutes) to re-orient to a primary task after a distraction such as an email. Efficiency can drop by as much as 40%.”

Whether students or teachers are able to fully combat this epidemic is yet to be seen, but there is reason to be hopeful, according to researchers, particularly if people are willing to put their devices away.

Guidance counselor Susan Burgess agrees that limiting immediate distractions can make a huge difference:

“Make sure you’re not surrounding yourself with things that are going to distract you, and put away phones and other distractions in a bag so that they’re not in right in front of your face or can be easily accessed.”